Go back to the main book page

Narrative Rationality and the Logic of Good Reasons

This chapter provides a theoretical basis for examining the tension between scientific and lay rationality that continues to undermine attempts to address such vital healthcare issues as vaccine hesitancy (Larson 2020) or lack of compliance with regulations and test regimes during a pandemic (Fancourt et al. 2020). Rather than treating different responses and attitudes towards particular issues as rational or irrational in purely scientific terms, the theoretical framework we discuss here acknowledges different types of rationality, and hence plural conceptualizations of evidence. In outlining this framework, the aim is to elaborate a nuanced and socially responsive approach to expertise and knowledge – an approach that can offer insight into the sources of controversy around medical phenomena such as COVID-19 and a more productive means of communicating medical information.

2.1. The Narrative Paradigm: Basic tenets

The basic assumption underpinning what has come to be known as the narrative paradigm is that “[n]o matter how strictly a case is argued – scientifically, philosophically, or legally – it will always be a story, an interpretation of some aspect of the world that is historically and culturally grounded and shaped by human personality” (Fisher 1987:49). Even a scientific argument or claim, however abstract, is ultimately processed as a story and interpreted not in isolation but as part of a particular narrative take on the world. In this sense, all knowledge is “ultimately configured narratively, as a component in a larger story implying the being of a certain kind of person, a person with a particular worldview, with a specific self-concept, and with characteristic ways of relating to others” (ibid.:17).

Importantly, our embeddedness in the narratives that constitute our world and within which we live our lives does not preclude an ability to reflect on, question and assess these narratives. We assess the narratives that surround us against the principles of coherence and fidelity, as discussed in detail later in this chapter. As such, we are all “full participants in the making of a message”, whether we are authors or audience members (Fisher 1987:18). The narrative paradigm suggests that we ultimately assess different versions of competing narratives on the basis of the values we believe each encodes and the extent to which they resonate with our own values and beliefs. This explains, for instance, the diametrically opposed responses we have witnessed to scientific arguments about the need to wear a face mask during the COVID crisis (see chapter 3). On the one hand these arguments are vocally rejected by some on the basis that the mandate to wear a mask encroaches on their personal freedom and is a form of control over their bodies; at the same time, others accept the mandate willingly and see compliance with it as a matter of moral responsibility to protect themselves and those they may come into contact with. Neither group can simply be dismissed as irrational. The narrative paradigm attempts to make sense of such responses through the concept of narrative rationality, understood as a “‘logic’ intrinsic to the very idea of narrativity” (Fisher 1985b:87). Narrative rationality asserts that “it is not the individual form of argument that is ultimately persuasive in discourse. That is important, but values are more persuasive, and they may be expressed in a variety of modes, of which argument is only one” (Fisher 1987:48; emphasis in original). Greenhalgh (2016:3) makes a similar point in the context of using narrative research in healthcare when she argues that “[s]tories convince not by their objective truth but by their likeness to real life and their emotional impact on the reader or listener”.

This is not the same as arguing that all knowledge is equally rational or true, or that any ‘good reason’ (in Fisher’s terms, as discussed below) is as good as another. The concept of narrative rationality merely suggests that “whatever is taken as a basis for adopting a rhetorical message is inextricably bound to a value – to a conception of the good” (Fisher 1987:107). Whether originating in a transcendental belief in universal human rights or in adherence to a specific religious stipulation, “a value is valuable not because it is tied to a reason or is expressed by a reasonable person per se, but because it makes a pragmatic difference in one’s life and in one’s community” (ibid.:111; emphasis in original). Our argument is that only by creating awareness about the specific values people adhere to and invest in their narratives that we can adequately understand why they believe in these particular stories. As such, the narrative paradigm provides a radical democratic ground for social political critique (ibid.:67). It refutes the assumption that rationality is a privilege of the few and the exclusive possession of ‘experts’ who (a) have specialized knowledge about the issue at hand, (b) are cognizant of the argumentative procedures dominant within the field, and (c) weigh all arguments in a systematic and deliberative fashion (ibid.). From the perspective of the narrative paradigm, all human beings are rational. While technical concepts and criteria for judging the rationality of communication can be highly valuable in the specialized contexts in which these concepts are developed, they do not represent absolute standards of truth. No community, knowledge or genres can have a final claim to such standards. Moreover, as soon as the expert “crosses the boundary of technical knowledge into the territory of life as it ought to be lived” (ibid.:73), he or she becomes subject to the demands of narrative rationality. When the medical expert, for instance, engages in public discourse regarding pandemic-related measures or in dialogue with patients about everyday health problems, he or she is obliged to leave the rationality of their technical community and submit to the narrative criteria for “determining whose story is most coherent and reliable as a guide to belief and action” (ibid.). Such a democratic understanding is a prerequisite to elaborating effective narratives that can enhance the reception of medical knowledge and reduce some of the sources of resistance and misunderstanding that continue to plague public communication during critical events such as pandemics.

The starting point for the narrative paradigm is that storytelling is the defining feature of humanity; we are homo narrans (narrating humans) before being homo sapiens (wise or knowing humans). The homo narrans metaphor is central to the narrative paradigm: it shifts the focus to the everyday, prereflective, practical aspect of being in the world in Heideggerian terms. The assumption is that it is “through our practical engagement with the world that a thing becomes what it is” (Qvortrup and Nielsen 2019:149). Because we dwell in narratives, we respond to (communicative) experiences instinctively before we begin to evaluate them consciously. Indeed, the narrative paradigm assumes that rationality itself “is born out of something prerational, an experience that in the very moment defies classification and explanation, but delivers us something to classify or explain after the fact” (ibid.:156). While traditional rationality is a skill that has to be actively learned and cultivated and – importantly – involves a high degree of self-consciousness, “the narrative impulse is part of our very being because we acquire narrativity in the natural process of socialization” (Fisher 1987:65). The narrative paradigm thus offers a way of conceptualizing the world in which “practice precedes theory” (Qvortrup and Nielsen 2019:149), and indeed Fisher presents narrative rationality as “an attempt to recapture Aristotle’s concept of phronesis”, or practical wisdom (1985a:350). In the context of healthcare, the narrative paradigm suggests that clinicians are instinctively guided first by the narratives they have come to subscribe to over time, some of which arise from their practical experience of delivering healthcare, and only secondarily by the evidence from controlled trials and other theoretically informed data. The same is true of a significant proportion of frontline healthcare workers in England (mostly Black and ethnic minorities) who continued to turn down the offer of vaccination when it was introduced in early 2021 (Sample 2021), despite having the same access to arguments explaining the importance of vaccination as their white colleagues (see Chapter 5 for a fuller discussion of this issue). Lay members of the public similarly adopt or shun the healthcare options available to them on the basis of how they fit into the narratives to which they subscribe and that constitute their sense of self, rather than on the basis of scientific evidence that they cannot, at any rate, directly assess for themselves. Ultimately, the logic of narrative rationality “entails a reconceptualization of knowledge, one that permits the possibility of wisdom” (Fisher 1994:21).

In understanding the scope of this claim, and some critiques of it discussed in the literature (e.g. Kirkwood 1992; see Chapter 6 for details), it is important to note the difference Fisher draws between narrative as paradigm and narrative as mode of discourse. “The narrative paradigm”, he explains, “is a paradigm in the sense that it expresses and implies a philosophical view of human communication; it is not a model of discourse as such” (1987:90). Narration here is to be understood as a conceptual framework rather than a text type or genre. It is also not a retroactive discursive phenomenon, that is, the act of telling a story, but a metaphor for living (Qvortrup and Nielsen 2019:152). Rather than seeing narratives as temporal wholes consisting of a beginning, a middle and an end, the narrative paradigm considers narration as an open-ended possibility. While the philosophical ground of the rational world paradigm is epistemology, that of the narrative paradigm is ontology (ibid.:146). The rational world paradigm functions through “self-evident propositions, demonstrations, and proofs, the verbal expressions of certain and probable knowing” (Fisher 1984:4). The narrative paradigm, on the other hand, is concerned with the primary mode of being in the world, with the way in which we instinctively and prereflectively embed any experience within a story or the set of stories that constitute our world in order to make sense of it. This is different from the specific form that a given discourse might take, whether it is a novel or a scholarly paper for instance. In the paradigm (rather than mode of discourse) sense, all forms of communication ultimately contribute to and can only be understood with reference to larger societal narratives. As a mode of discourse, on the other hand, we can distinguish between narration, exposition, argumentation, and various other genres and explore their appropriateness or otherwise for communicating health and other types of knowledge. Fisher suggests, for example, that “narration works by suggestion and identification” whereas “argument operates by inferential moves and deliberation”; from the narrative paradigm perspective, “the differences between them are structural rather than substantive” (1984:15). As Roberts (2004:130-131) puts it, “[p]eople are not essentially arguers, but rather storytellers, and sometimes those narratives merely take the form of argument”.

2.2. Narrative Paradigm vs. Rational World Paradigm

Before we discuss how the narrative paradigm might help us appreciate some of the tensions and concerns that continue to hamper the delivery of healthcare in many contexts, it is useful to explain how it differs from the type of rationality traditionally used to assess arguments and responses to them, including in medical and scientific contexts.

The narrative paradigm assumes that all human beings are capable of reasoning, irrespective of their level of education or training. In some ways, society already acknowledges the inherent (narrative) rationality of all humans, their innate practical wisdom: it does so when it appoints lay members of the public to juries that have the power to decide the fate of defendants, and when it acknowledges the right of all citizens to vote in elections, irrespective of their background or education. In such contexts, truth is associated with identification, not deliberation – with what ‘rings true’ among voters and members of the public. In most other contexts, however, rationality is associated with a scientific, empirical approach to knowledge that assumes that (educated) people are able to assess arguments by applying the standards of formal and informal logic. This view of rationality focuses on the world as a set of puzzles that can be solved through inferential analysis and “empirical investigations tied to such systems as ‘cost-benefit’ analysis”. “Method, techniques and technology” are the means used by this type of rationality to solve problems; “efficiency, productivity, power, and effectiveness are its values” (Fisher 1994:25). True knowledge is understood to be objective: “the result of observation, description, explanation, prediction, and control” (ibid.). In medicine, this type of rationality is often frequency-based, in the belief that “‘although we can’t predict the future for the individual case, we can be “usually” right (eg, 95% of the time)’ as long as events or cases are frequent enough” (Wieringa et al. 2018a:88; citing Hacking 2001). Health care decisions, the argument goes, should therefore be guided by large amounts of data, ideally collected through systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Fisher asserts that this scientific, empirical view of rationality “informs the mind-set of researchers and consultants for virtually all levels of decision making in every social, political, educational, legislative, and business institution in society” (1994:25). It constitutes the dominant way of understanding reason that has prevailed in the Western tradition since Plato: as “an achievement of training, skill, or education” (Stroud 2016:1). In medicine, it reached its point of culmination in the evidence-based medicine (EBM) paradigm, which argues that healthcare decisions should be grounded in high quality medical research. EBM provides tools to distinguish between high and low quality evidence and to appraise research evidence based on scientific rationality (see chapters 1 and 6 for a more detailed discussion). The knowledge produced by this type of rationality tells us what is “instrumentally feasible and profitable” but not how to address issues of justice, happiness and humanity (Fisher 1994:25). It is ‘knowledge of that’ and ‘knowledge of how’ but not ‘knowledge of whether’ (ibid.); it “gives one power but not discretion” and “drive[s] out wisdom” (ibid.:26):

Medical doctors know that by using certain technological devices they can keep one alive even when the brain is ‘dead’, They know how to do this. The question of whether they do this is beyond their science. … Doctors and scientists, as technicians, may dismiss, ignore, or relegate this sort of knowledge to others – it is not their business – but they cannot do so without denying their humanity. (ibid.:25)

At the point where medical doctors cross the boundary of technical knowledge – where knowing that and knowing how dominate – and enter “the territory of life as it ought to be lived” (Fisher 1987:73), they are ‘off-duty’. They then pass from the domain of facts to the domain of values, from what they know to what they should do (Lonergan 1992; Engebretsen et al. 2015). Questions such as whether to impose lockdowns or make vaccination mandatory are not strictly scientific but political. In relation to such questions, the expert takes on the role of a counsellor “which is, as Walter Benjamin notes, the true function of the storyteller” (Fisher 1987:73). Outside the controlled context of an experiment or trial, practical problems also become the focal point for competing expert stories that address the issue from different angles. The question of whether or not to impose lockdowns or make vaccination mandatory, for instance, might be framed very differently from the point of view of immunologists, psychiatrists, sociologists and educational scientists. The narrative paradigm asserts that none of these experts can “pronounce a story that ends all storytelling” (ibid.).

Narrative rationality attempts to combine knowledge of that and knowledge of how with knowledge of whether, and supplements them with “a praxial consciousness” (Fisher 1994:25). Because values are central to this view of rationality, the operative principle of the narrative paradigm is “identification rather than deliberation” (Fisher 1987:66). Thus, for example, despite being “told from a subordinate position in the knowledge hierarchy”, narratives of natural childbirth that draw on “subjective, experiential and visceral knowledge” (Susam-Sarajeva 2020:47, 48) can challenge institutional narratives of progress, science and modernity precisely because they persuade through identification rather than logical argumentation. In the words of Ina May Gaskin, author of Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth,

[stories] teach us the occasional difference between accepted medical knowled¬ge and the real bodily experiences that women have —including those that are never reported in medical textbooks nor admitted as possibili¬ties in the medical world. […] Birth stories told by women who were active participants in gi¬ving birth often express a good deal of practical wisdom, inspiration, and information for other women. (Gaskin 2003, cited in Susam Sarajeva 2020:48)

Hollihan and Riley’s study of parents of difficult children who came together in a network of parental support called ‘Toughlove’ found that participants felt that the “rational world, with its scientific notions of child-psychology … did not speak to them” (1987:23), whereas the Toughlove story, which lay the blame on their children and encouraged them to adopt tough measures to discipline them, “resonated with their own feelings that they were essentially good people whose only failing had been that they were too permissive and not as tough as their own parents had been” (ibid.).

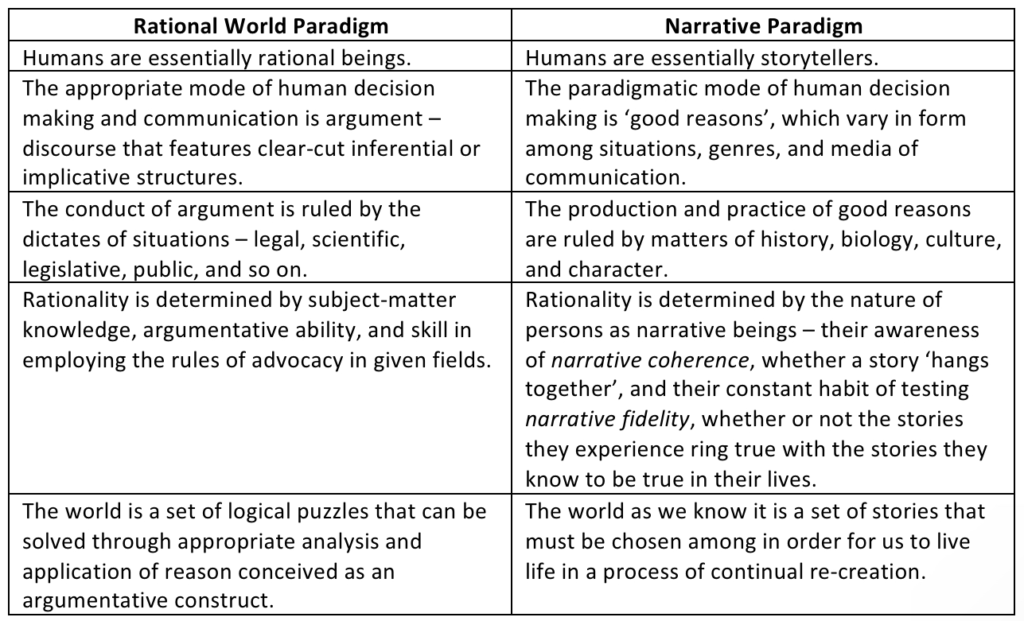

Narratives, then, compete to the extent that they are able to connect and resonate with the audience’s values and sense of self; rational arguments, on the other hand, compete on the basis of the extent to which they follow the rules of logical inference. The rational world paradigm assumes that “the primary mode of decision-making and judgments in human communication is argument” (Stroud 2016:1); the narrative paradigm posits that it is “the provision of good reasons” (ibid.:2), which, as we explain shortly, concerns the implicit and explicit values encoded in any message, whatever form that message takes. Narrative rationality assumes that all human beings are rational in the sense of being able to think and to hold views about various aspects of life; that they are “reflective and from such reflection they make the stories of their lives and have the basis for judging narratives for and about them” (Fisher 1984:15). It explains how people come to “feel at home (dwell) in multiple stories, imbuing subsequent actions with intrinsic meaning” (Qvortrup and Nielsen 2019:159). It is not dependent on argumentative competence in specialist fields nor on formal education, although Fisher does recognize that education can make us “more sophisticated” in understanding and applying the principles of assessing narratives from the perspective of the narrative paradigm (1984:15). In essence, however, narrative rationality has its own logic – the logic of good reasons – which ultimately subsumes rather than displaces traditional rationality (Fisher 1987:66). Table 2.1 sums up the differences between the rational world paradigm and the narrative paradigm as outlined in Fisher (1994:26, 30) and elsewhere.